Candle Craft 6: Matriarch, Patriarch, Scholar, and Fool

By Royal McGraw

Royal McGraw has written professionally for film, television, comics, and games for over 20 years. He led development on the mobile smash hit Choices: Stories You Play and currently serves as CEO of Candlelight Games.

Welcome! This is the sixth installment of a multi-part series intended to provide you with 10 Quick And Actionable Adjustments that you can make to your own writing process to improve your storytelling. Some of these process adjustments will be strategic, offering suggestions to improve how you think about storytelling from a big-picture standpoint. Some of these process adjustments will be tactical, offering suggestions to improve how you think about tackling scenes or even individual lines of dialogue. In all cases, these lessons have been hard-won, gleaned from over 20 years of experience writing across a variety of different mediums.

In the previous installment of Candle Craft, we discussed the theory of the Story Mind. According to this theory, the characters, plot, theme, and genre of a well-written story dramatize an entertaining argument.

However, one shortcoming of Story Mind is that the approach can be taken too far, yielding characters that sound too similar. In this installment of Candle Craft, we’re going to explore a classic method to ensure that your character reactions (and voices) are distinct.

This technique is called Matriarch, Patriarch, Scholar, and Fool (MPSF).

What is Matriarch, Patriarch, Scholar, Fool?

In an episode of How Was Your Week? with Julie Klausner (and many other interviews), Mitchel Hurwitz of Arrested Development fame describes a writing paradigm he refers to as “Matriarch, Patriarch, Scholar, Clown” as being a dominant fixture in literature and pop culture, especially sitcoms – from Golden Girls, to Seinfeld, to Leave It To Beaver.

Note: even though Hurwitz uses the term “Clown” instead of “Fool”, the technique is the same. I’ll be using the term “Fool”, as it’s how I learned the subject matter.

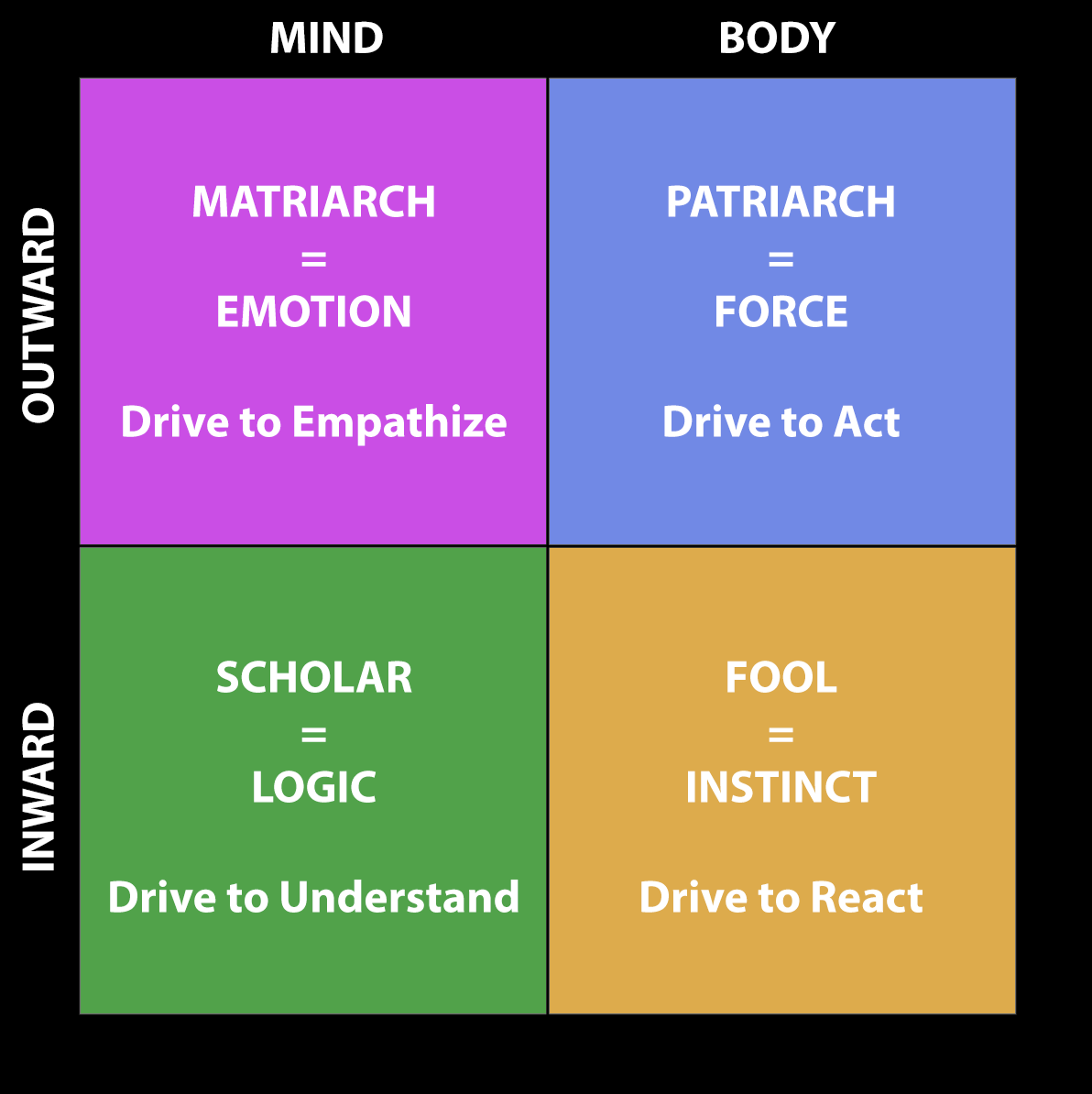

In this literary paradigm, there are four defined reactions to a situation or problem that can be expressed: Emotion, Action, Logic, and Instinct.

These reactions are distributed across the core cast as follows:

The Matriarch responds emotionally. She asks, “What do they feel?” or “What emotion drives them?”

The Patriarch responds forcefully. He declares he’s going to fix the situation through immediate and direct action.

The Scholar responds logically. He asks, “What do they want from us?” or “What chain of events brought us to this point?”

The Fool (or Clown) responds instinctively. He says what he (or we, the audience) are thinking or feeling. He might jest that the bad guy has a funny hat, or he might remind everyone on the team that they haven’t eaten in a while.

Two big notes on the Fool:

The Fool is not dumb, or even necessarily trying to be funny. Plenty of “Fools” do not recognize themselves as jokesters. What matters is the instinctive (and truthful) situational response.

The Fool possesses some amount of “jester’s privilege”, the ability and right of a jester to talk and mock freely without being punished.

Classic Examples of MPSF

In his interview, Hurwitz called out numerous examples of this formula in sitcoms, but this paradigm it’s absolutely everywhere, especially in formats that require ongoing episodic storytelling. The term “sitcom” derives from “situational comedy.” Each new episode presents a situation. The situation is what characters react to, and what we enjoy watching is characters react.

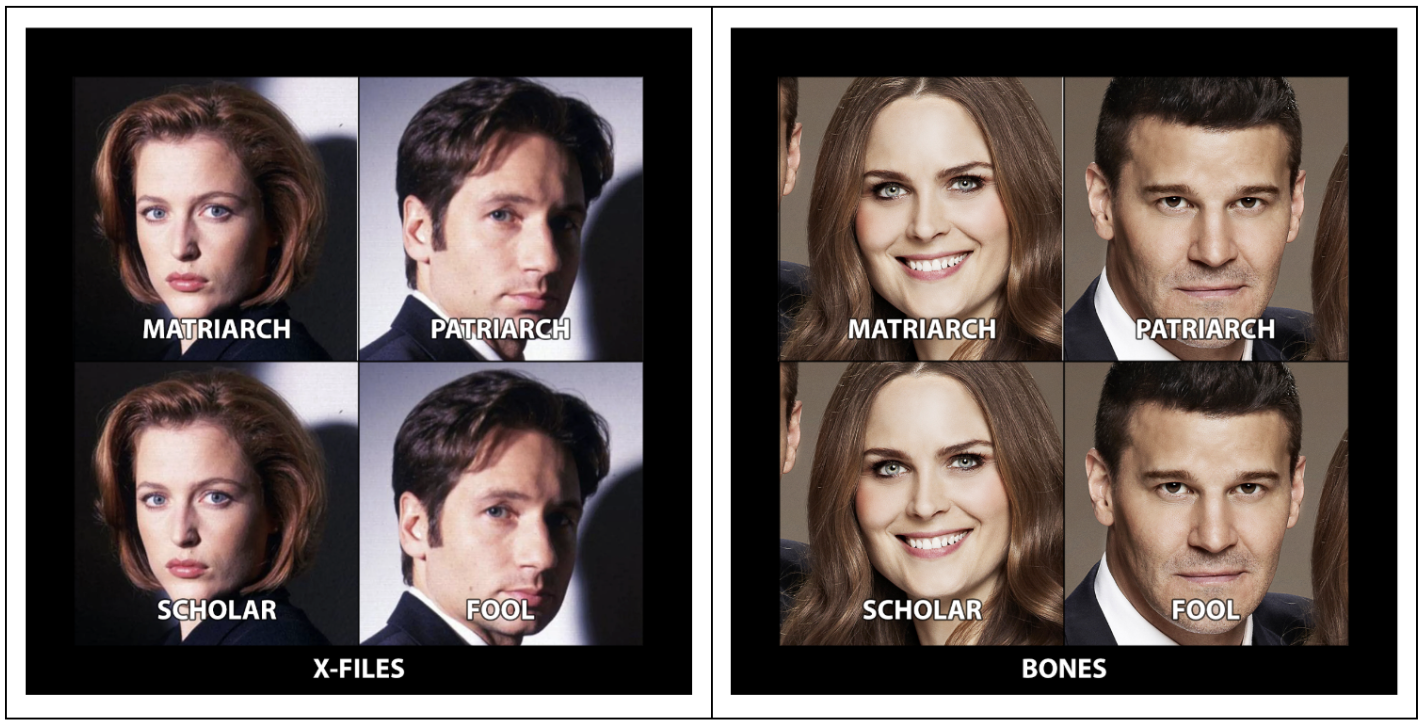

Procedurals – and their close cousins like ER, House, The X-Files, Buffy The Vampire Slayer or Supernatural – are “situational melodramas.” Again, the situation – be it a crime, medical emergency, or a Monster of the Week – is what characters react to, and what we enjoy watching is how characters react.

Because MPSF provides a template for character reactions, it’s a natural fit for these kinds of episodic formats. As a consequence, nearly every long-running television series (or book series) has adopted this formula intentionally or instinctively.

Two-Handers

Some shows and books only have two primary leads. In these cases, the traits are commonly distributed between those two leads.

As you can see in both examples, the Patriarch and Fool archetype are paired. This is very common in episodic television, and this leaves Matriarch and Scholar archetypes to be paired within the second lead. You can view this as the physical domain – action and reaction – separated from the interior domain – emotion and logic.

But of course, most of these shows add in additional castmates for flavor. Looking at Supernatural, we can see how creators might approach different cast scenarios.

By putting additional cast members into the mix, creators are able to play toward certain facets of characters within specific scenes or even seasonal arcs.

This brings us to something very important when talking about MPSF: exceptions are the rule!

Exceptions are the Rule in MPSF

Even in the classic MPSF examples shared above, you’ll almost certainly recall a moment when a character reacted unlike the archetype listed. That’s as expected! No well-written character is completely one-dimensional, and the longer a series goes, the more multi-dimensional each character becomes.

Additionally, cast changes – additions or subtractions, even just within scenes of the same episode – might favor characters playing more strongly to one core facet than another. The key is to be aware of your characters – even something as simple as a stack rank of their reactive tendencies can be useful if you’re writing to a deadline or for maximum voice differentiation.

Moving Forward

Pay attention to the media you watch, and see if you can see how creators leverage MPSF in their work. Now that you’re aware of this pattern, you’ll see it everywhere.

In terms of your own writing, look at your core cast, and see if they make sense within this paradigm. If so, great! You now have additional insight into how to craft character reactions.

TIP #5: Use Matriarch, Patriarch, Scholar, Fool to ensure your characters react to events differently

This isn’t the only way to look at character voice, and sometimes you need to break things down line by line. Next time, we’ll look at another method to do just that: The Spider Test.