Candle Craft 12: Unity of Effect

By Royal McGraw

Royal McGraw has written professionally for film, television, comics, and games for over 20 years. He led development on the mobile smash hit Choices: Stories You Play and currently serves as CEO of Candlelight Games.

Welcome! This is the 12th installment of a multi-part series intended to provide you with quick and actionable adjustments that you can make to your own writing process to improve your storytelling.

In the previous Candle Craft, we discussed how to plot compelling scenes and narratives using the “But, Therefore” method. As we learned, this method replaces passive sequencing with active cause and effect. Each “but” adds tension; each “therefore” creates forward motion.

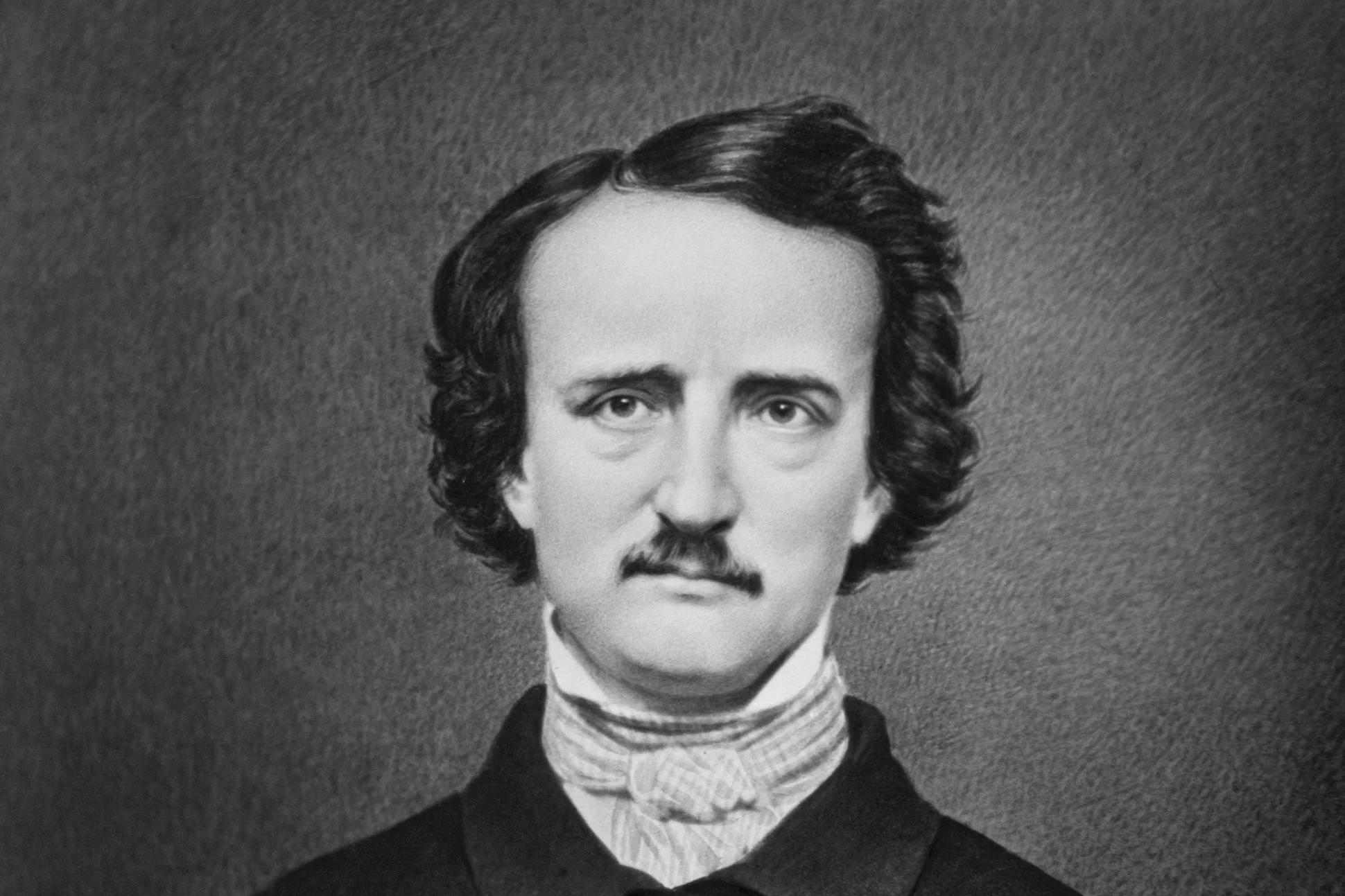

Now that our scenes move logically from one to the next, the next challenge is ensuring they all feel like parts of the same living body, brought to life by a single tell-tale heart. This method, first described by Edgar Allen Poe, is called Unity of Effect.

Poe and the Foundation of Unity of Effect

For those of you who aren’t familiar with Edgar Allen Poe, Poe was the first truly great American horror writer and credited as the inventor of the entire detective genre. We remember him now for poetry like The Raven and short stories like The Fall of the House of Usher and The Murders in the Rue Morgue.

Poe also wrote a brief essay on how he approached his fiction and poetry called The Importance of the Single Effect in a Prose Tale. He also elaborated on his poetic craft in The Philosophy of Composition. We’re going to spend a little time with these essays and explore the writing principles that Poe built into them.

The Mathematics of Emotional Impact

Let’s start with some quotes that capture the big ideas that Edgar Allen Poe advanced as narrative guidance within his essays.

“It appears evident, then, that there is a distinct limit, as regards length, to all works of literary art—the limit of a single sitting.

My next thought concerned the choice of an impression, or effect, to be conveyed: and here I may as well observe that throughout the construction, I kept steadily in view the design of rendering the work universally appreciable.”

Antiquated language aside, Poe is saying that he starts with two important considerations:

How long do I have with my audience?

What do I want my audience to feel?

Poe is concerned with the length of the work because he believed that there was an almost mathematical perfection that could be derived via careful craftsman – an ideal balance of length against audience impact. Too short, and the work wouldn’t have enough time to build up to a heady emotional climax. Too long, and the emotional impact would be blunted.

Even in branching or choice-based narratives, Unity of Effect holds. Unity of Effect doesn’t prevent branching; in fact, done right, it guides the emotional purpose of each choice a player makes. All of this is the emotional impact Poe was talking about, the precise calibration of length to feeling.

Now that we’ve identified what we want the audience to feel, the question becomes: How do we create that feeling on the page?

Writing Toward Emotion

This is the guidance that Poe gives us toward achieving Unity of Effect:

“A skilful literary artist… having conceived, with deliberate care, a certain unique or single effect to be wrought out, he then invents such incidents… as may best aid him in establishing this preconceived effect. ”

Here again, Poe is talking about how he approaches authorial intention. If Poe has decided that he wants his audience to feel “dread”, he creates scenarios that do just that.

On the one hand, that’s pretty obvious… horror movies contain moments of horror, rom-coms contain romance and comedy… Are we just talking genre?

No, not exactly. Genre is the container. Unity of Effect is the specific flavor.

Human emotions are so much more nuanced than just “horror” viewed through the flattening lens of genre. Think about the words more closely: is the emotion “horror” the exact same as “dread” or “anxiety” or “fear” or “disgust”?

We can go even deeper. The Wes Craven movie Scream centers on the very specific emotion of “fun with horror movies.” How does Scream achieve this?

The very first scene functions as a slasher movie kill wrapped up in a tricky pop culture horror quiz. “Do you like scary movies?” the movie asks. The movie does, and it serves as a love letter to the whole genre.

Poe pushes his idea of Unity of Effect even further when he says:

“If his very initial sentence tend not to the outbringing of this effect, then he has failed in his first step.”

Does the opening scene of Scream solve for Poe’s Unity of Effect? Absolutely.

But importantly, Unity of Effect is not just about horror. Pixar films are masters of Unity of Effect. Every emotional beat in the film Inside Out reinforces the central feeling of “making peace with sadness” – a complex, bittersweet, highly specific emotion.

Sharpening the Effect

There are two ways to carry Poe’s Unity of Effect into our own work. They are inclusion and exclusion. In his essay, Poe frames the idea as inclusion – “he then invents such incidents.”

This is great, but I’d offer that exclusion is actually more useful. By determining the emotion we want our audience to feel we can challenge our first draft with pointed questions: “Does this scene either evoke the desired feeling or build directly toward another scene that evokes the desired feeling?”

This is where Unity of Effect stops being theory and becomes a powerful editing tool. Ask of every scene:

Does it evoke the core emotion?

Does it build toward a moment that does?

Does it disrupt or dilute the intended effect? (Cut it.)

TIP #8: Use “Unity of Effect” to test your work. Find the single specific emotion your work intends to evoke and ensure every narrative element either builds toward that emotion or elicits it directly.

Going Forward

Now that you know how to guide your work to evoking a single coherent emotional response, we’re going to review all of our narrative tips again within the framework of a unifying theory. Up Next: Fractal Storytelling.